PATIENT INFORMATION A. VOSMAER

PATIENT INFORMATION A. VOSMAER IKAZIA HOSPITAL

PERTHES’ DISEASE

Perthes’ disease has something in common

with gunpowder: they were both discovered at the same time in different parts

of the world. Around 1910, three doctors (Legg in America, Calvé in France and Perthes

in Germany) all described a condition in which a child would walk with a limp

and experience pain in the groin, thigh or simply the knee and have restricted

movement (especially splaying the leg and turning it inwards) caused by

impaired blood supply to all or part of the femoral head (hip).

The

primary cause is still unknown, despite extensive literature on the subject.

It is a condition in which the bone structure

of the femoral head can restore itself, but the shape is not always correct.

The problem is therefore one of femoral head malformation, and this is

the aspect on which all attention must be focused. The condition starts between

the ages of three and twelve, in most cases between five and seven. It

affects four times as many boys as girls, and occurs on both hips

in 10 to 15% of patients. This means that both hips must then be monitored. The

prevalence of the condition varies markedly throughout the world and

within countries, towns and even districts. The highest prevalence ever

described was in the centre of

The question is whether Perthes’

disease is a) part of a general process or b) a local abnormality

of the hip alone. Arguments in favour of it being part of a general process

affecting the entire body include the fact that children with Perthes’ disease often also have other (minor)

abnormalities, such as shorter forearms and feet, and that their skeletal

age may lag by a few months to a few years (though they later catch up).

Inguinal hernias are often observed as well. It has recently been discovered

that clotting disorders may be more common in children with Perthes’ disease and their close relatives, but this has

not yet been definitely established. Perthes’ disease

occurs much more frequently in families in which someone smokes (but it

would be going much too far to assume that this is the cause). The illness does

run in families, but hereditary factors have never been demonstrated.

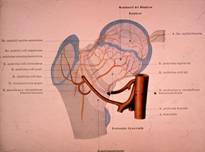

What occurs at the local level is impairment in blood supply, causing (temporary) destruction of bone

tissue. Microscopic examination has revealed that vascular occlusion has to

occur several times before the disease can develop. At the age at which

children develop Perthes’ disease, the femoral head

receives blood from only a small number of blood vessels. These blood vessels

are very sensitive to pressure, especially if there is fluid in the joint.

Tilting the hip slightly reduces the pressure. This is also the most

comfortable position if the hip is irritated, i.e. if there is fluid in

the hip, the hip is painful, and movement is restricted. In this case, bed rest

with the legs slightly elevated is better than bed rest lying flat.

What occurs at the local level is impairment in blood supply, causing (temporary) destruction of bone

tissue. Microscopic examination has revealed that vascular occlusion has to

occur several times before the disease can develop. At the age at which

children develop Perthes’ disease, the femoral head

receives blood from only a small number of blood vessels. These blood vessels

are very sensitive to pressure, especially if there is fluid in the joint.

Tilting the hip slightly reduces the pressure. This is also the most

comfortable position if the hip is irritated, i.e. if there is fluid in

the hip, the hip is painful, and movement is restricted. In this case, bed rest

with the legs slightly elevated is better than bed rest lying flat.

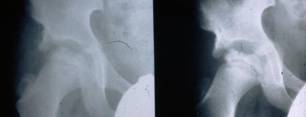

The diagnosis is established on the basis of two X-rays of the pelvis: one anteroposterior view and one Lauenstein (frog-leg) view.

The diagnosis can easily be missed if only an anteroposterior view is examined. The first abnormality

seen on the X-ray is widening of the joint space (fluid), then loss

of height in the femoral head (flattening) and bleaching (bone

tissue dying off). The frog-leg X-ray often reveals a fracture line

below the surface of the femoral head. This line indicates how extensive the process

is at an early stage.

The condition then goes through the following

phases:

- Necrosis phase

- Fragmentation phase

- Recovery phase

In the necrosis phase, bone tissue dies off and

the head of the joint looks whiter on the image. In the fragmentation phase,

the head appears to crumble. This is not really happening, because cartilage

(which does not show up on an X-ray) is temporarily taking the place of the

bone which has been destroyed. It is also at this stage that the softer head

can easily become deformed. Normal bone tissue returns in the recovery phase.

It takes three to five years for the disease to pass through these three

phases. The final outcome will only be known once the child has stopped

growing.

The extent of the process can be classified according to the four Catterall grades, which are important for the prognosis.

Grade 1: Grade 2:

Grade 3: Grade 4:

Grade 1 has the best prognosis, as only a small

part is affected. Therapy is not

necessary. Grade2: less than half of the femoral head is involved. Grade 3: 3

quarter of the femoral head is involved. Catterall

grade 4, in which the entire femoral head is affected, has the worst prognosis.

So we see that the severity of the condition varies markedly. To have an idea

of the prognosis it is useful to know whether less or more than half of the

femoral head is involved.

There are also a number of features that can be detected by X-ray that are associated with a poor prognosis. These features are known as “head at risk signs”.

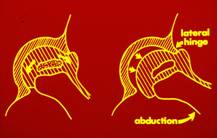

The most important risk sign is when the femoral head emerges from the socket. If this happens, it is important for it to be returned to the socket as good as possible. While the vulnerable, malleable femoral head remains within the protection of the socket, which acts as a mould, it will retain its rounded shape, especially if the hip is kept mobile. It is like holding a lump of clay in your hands: if you move it, it becomes round, but becomes flat if you keep it still.

If the femoral head is not properly positioned within the socket for a prolonged period, a dent can develop in the head caused by pressure exerted by the edge of the socket. This changes the hip from a ball-and-socket joint into a hinged joint, making it difficult for the individual to splay and rotate the legs.

The height of the outer part of the femoral head is critical to the course of the disease: the flatter it becomes, the worse the final outcome is.

Other investigations can be performed in addition to standard

X-rays. An echogram is often taken at the start of the disease to

ascertain whether there is any fluid in the joint. The width of the joint space

on the standard X-ray image will also indicate this.

Other investigations can be performed in addition to standard

X-rays. An echogram is often taken at the start of the disease to

ascertain whether there is any fluid in the joint. The width of the joint space

on the standard X-ray image will also indicate this.

A bone scan will reveal bone decomposition and formation. A decline in bone activity will show up on a bone scan a few weeks or months before anything can be learned from an X-ray. However, as soon as more (repair) bone activity starts to take place, the bone scan will for a time show the situation as normal, which is not the case. So the indication for a bone scan is limited.

Very early diagnosis has little impact on therapy in the case of Perthes’ disease. This is also true of an MRI scan, but this procedure does offer the advantage of allowing doctors to estimate how extensive the condition is at an early stage, and this does have consequences for treatment. While the abnormalities remain minimal on a standard X-ray, treatment usually involves controlling the symptoms of the irritated hip.

An arthrogram (an X-ray image taken after injecting contrast agent into the joint) may be needed before any surgery is performed to assess the cartilaginous head, which remains rounded for quite a long time, and also to find out the best position for the femoral head within the socket.

The longer-term prognosis (the

likelihood of arthrosis, or wear) depends on

femoral head malformation when the child has stopped growing. This in turn

depends mainly on the age at which the disease develops: the older the

patient is at the start of the disease, the less time the hip has to recover

while he or she is still growing.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that a

child who contracts the disease at a young age will always recover well.

Malformation depends on the extent of the process and on the risk

signs, especially whether the femoral head comes out of the socket. If the

outer edge of the head retains its height that improves the prognosis.

The main aim of treatment for Perthes’ disease is therefore to prevent the head emerging

from the socket. In the early days, when still dealing with an irritated hip,

treatment will comprise short periods of bed rest or avoiding putting strain on

the hip. This is intended mainly to relieve symptoms. In the next stage of the

disease, symptoms are often mild but the disease is still progressing and the

patient will have to pass through all the phases.

Treatments

vary, as the severity of the condition (extent of the process) can be very

different from one patient to another. In many cases, it will simply involve checking

whether the femoral head is threatening to emerge from the socket. The only way

of assessing this accurately is by X-rays.

Many forms of treatment have been applied in

the past, but these often appeared to make no difference to the disease process

when compared with giving no treatment. According to Catterall,

60% of children who received no treatment had a good outcome, so any therapy

must achieve a higher percentage score. Measures aimed at taking pressure off

the joint, such as extended bed rest (sometimes in hospital), crutches,

wheelchairs and braces, do not always appear to help. Treatment is usually

based on the principle of placing the malleable femoral head in the best

position in the socket. The position adopted in most cases is to have the leg

splayed, slightly bent and slightly turned inwards.

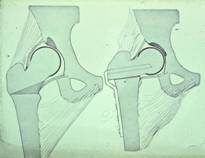

Surgery can be considered if the femoral head is

threatening to emerge from the socket and non-surgical techniques have not

proved successful. Removing a small wedge of bone underneath the femoral head

can allow it to be replaced in an ideal position in the socket. The benefit is that the patient will be able

to move the hip freely and put (some) weight on it once the bone elements have

knitted together eight weeks later. This will continue to be the case

throughout the entire disease process. Another advantage is that this operation

considerably reduces pressure on the hip joint.

There are nevertheless some drawbacks: a) the

leg becomes slightly shorter, though it may catch up as the patient grows; b)

the plate inserted to fix the joint will have to be removed at some point; and

c) the patient will have a scar.

Hip socket enlargement may be suitable for

children who develop the condition after the age of eight or if the hip is so

malformed that the femoral head cannot be adequately re-inserted into the

socket. This procedure involves creating

a roof on the socket to cover the protruding femoral head. Other operations can be performed on the

pelvic side of the joint, altering the position of the socket. But this increases pressure on the head,

which is not desirable, and does not enable as much correction. This procedure

is carried out less frequently.

None of these therapies guarantee a normal hip

(the diameter of the head is often somewhat greater, but this does not lead to

earlier wear). Some orthopaedic specialists tend to give no treatment, possibly

as a result of disappointing experiences. We have learned from the past,

though, that inaction does not always lead to good results (only 60%). Serious

cases do benefit of an operation, provided that the correction is at a

relatively early phase of the disease (i.e. not in the healing phase) and to a

sufficient amount. When the femoral head emerges from the socket the

orthopaedic surgeon has to decide for which child operation is the best option

based on the above mentioned criteria.

It is difficult to compare results from the literature, as different criteria are used to define a good, moderate or poor outcome, partly because there are so many X-ray evaluation techniques.

Sometimes one author seems to achieve an even

better result than another. The main point is whether the hip fits well in

the socket, is nicely rounded and not too flat (i.e. loss of

height).

Another important point to bear in mind is that although there is some malformation, it does not usually start to develop wear until quite late (usually after the age of 50), and a new hip prosthesis can always be fitted at that stage. Symptoms of pain and restricted movement can occur at a relatively early age, however, which is why it is so important to monitor a child with Perthes’ disease closely.

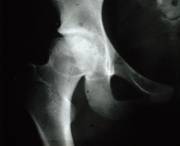

Arthritis at 66th years of

age.

This patient at 64 years of age didn’t have any sign of arthritis, even with an abnormal hip which fits well into the round cup.

At 12 years of age, Perthes disease started but was not treated adequately. At 27 years of age, the form of the head was abnormal and wear of the hip has started. At 46 years of age, severe wear has occurred.

Many articles have been published on this

condition since the first ones which appeared around 1910. Our understanding

has changed over the years, but the true cause still remains a mystery.

A. Vosmaer, orthopaedic surgeon

Montessoriweg 1

3083 AN

The